The Conlang Blog: Oracular Kallerian

all posts about the Kallerian Language Family can be found here.

Last week I talked about PCSK (Proto-City-State Kallerian) and some of the design elements I used when creating the language. (More on language creation itself here.) The purpose of PCSK was to create a basic foundation for other languages to branch off from—but I still wanted to use it in the novel. Enter Oracular Kallerian.

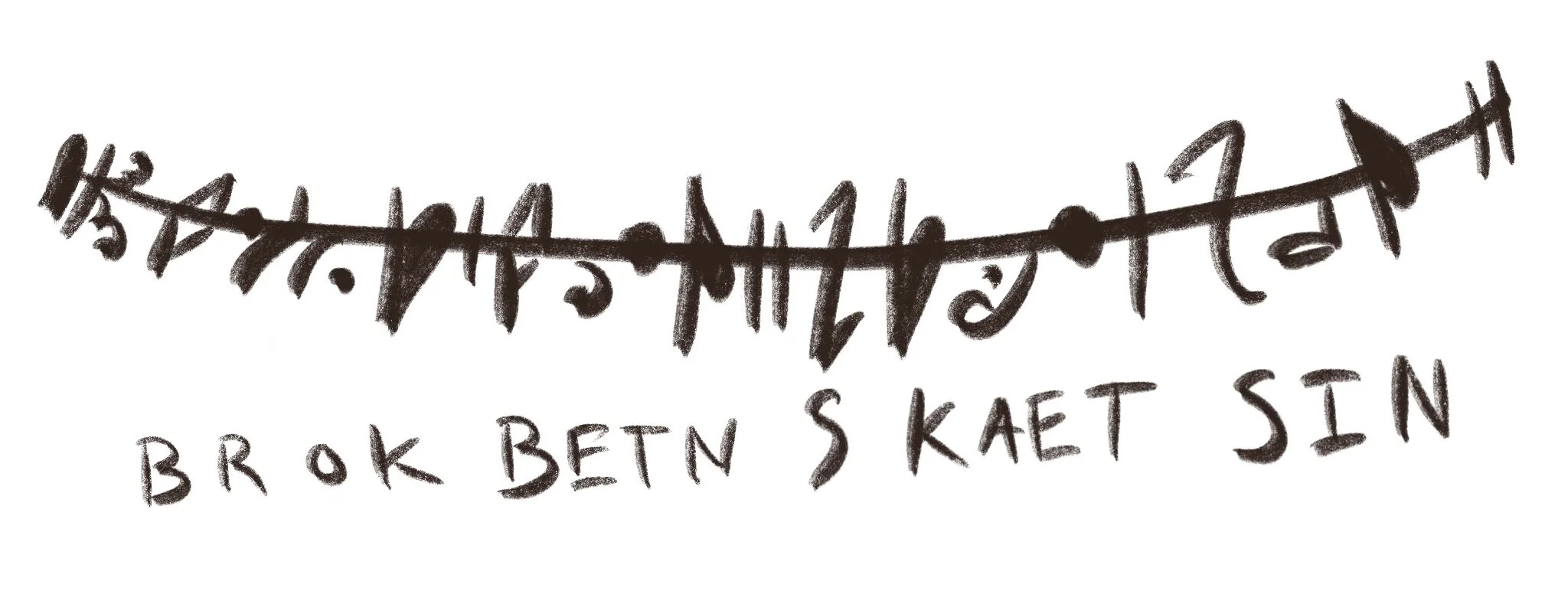

brok betn/skaet sin

”broken music'/shattered song”

4.10, Bell Prophet, reproduced from the rim of the Atmospheric Bell (English text added for clarity).

There are two schools of thought regarding oracles on Kalleria. One school says that oracles are absolutely useless: their prophecies are so convoluted with allusions and references and metaphors that make sense to no one but the oracle that it’s impossible to read a prophecy in a way that conveys any sort of meeting before the prophesized event happens. The other school insists that it is possible, that there are certain patterns the prophets use both culturally and individually, and that it’s a lifetime of work but one can make certain things out.

(Star Trek fans may recognize the source of inspiration for this concept: the episode “Darmok”, in which the Tamarian language proved untranslatable by the universal translator due to its reliance on metaphors and allegories. For obvious reasons it’s my all-time favorite episode, and I had to try out the idea, only I made it less scrutable and kept it in the original language of the speakers.)

The oracles themselves are surprisingly silent on the matter, although jokes are made that if they did speak up, no one would understand them anyway. Before the events of the novel, oracles tended to run away from their home cities and gather in the religious community, the Floating Papacy, where they lived out their days writing and speaking among their own kind. Not all of them ran, but those who stayed behind often lost the language skills of their own time, reverting to PCSK without a teacher, and eventually speaking only in the Oracular dialect.

Sagape, the Nation of Sky’s only living prophet, is quoted as saying when she was younger that this comes from a slow understanding of the poetry of words, and a realization that common language will never be as precise as allegory.

Then again, she also wrote this:

Bethasne; Staeoras ke Klefas, [nares thre ke aides fef ebatras, sinil klefassen so.]/Saer fibras ekaeldas./Hab lakassen bleurhe, hab an finas, hab sero finas./Far e nin, far e nin./Enta dyn, enta dyn.

Brotherless, Staeoras and Klef, ebatras of the third month of the fifth year, like keys untrue./The violins, all dry: yet clocks still weep, yet the first priest, yet the last./Four of nine, four of nine:/Out of time, out of time.

9.032, Sagape, reproduced text damaged by ink spillage. (Note: Caleb e’Batras apologizes and is working on a new reproduction.)

This is colloquially known as Caleb’s Prophecy—Caleb being a protagonist who is somewhat unusually specified in the prophecy via his birthday. The rest of it is completely inscrutable. “Yet the first priest, yet the last” may refer to a prophecy concerning the last priest of the Floating Papacy, but that prophecy simply states that he will not die by drowning. Weeping clocks may refer to a tradition in the Democracy of the Clock where a dead person’s timepiece is left at the location of their demise, and is not removed until the clock stops ticking.

Staeoras and Klef are Romeo-and-Juliet figures in literature. Four of nine could be anything, from days of the nine-day week to a set of collectible porcelain dolls. Out of time could mean the end of the world or a burnt dinner.

How do any of these pieces fit together? Caleb has spent most of his life trying to figure this out— and so far he’s come up with nothing. Most of it gets explicitly revealed over the course of the novel; some of it requires a bit of a deeper reading.

I’ve had far too much fun with this. Bits of prophecy are scattered throughout the book, carved into ancient artifacts or found on remnants of the world that was. It’s also offered me a chance to show the cultural side of the world—the mythological heroes, the songs, the traditions, the colloquialisms—in a natural way that wouldn’t really work otherwise.

The third fully-fleshed-out member of this family is NSK, Nation of Sky Kallerian, which is actively spoken by the majority of the main characters. Unless I get really excited about the Asher dialect, that’s probably coming up next.

![Bethasne; Staeoras ke Klefas, [nares thre ke aides fef ebatras, sinil klefassen so.]/Saer fibras ekaeldas./Hab lakassen bleurhe, hab an finas, hab sero finas./Far e nin, far e nin./Enta dyn, enta dyn. Brotherless, Staeoras and Klef, ebatras of the t…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5977d3d1d2b8576d2ca57a83/1601383657823-7BSZXK6S10BMMWJWEFZB/Sagape+9-032_PCSK_Oracular.png)